A historical biography – is this something for me?

For those who are interested in a unique biography, and are open to discovering something new, then this audience shouldn’t be disappointed. I explain in simple to grasp terms, what’s going on and why. Quite often, books make an assumption that you have a good understanding of history, or naval history in this case. I wrote this book without this assumption, so there’s plenty of descriptions, explanations and details, to ensure that everyone can understand not just Wim’s experiences, but the background and context.

Let’s face it, most people have heard of the Burmese railway being built by POWs in the second world war. The Burmese railway is more likely to be cited in our schoolbooks, and was made famous in a film. However, the Sumatran railway, has its own story to tell, which seems to be more neglected in the history books.

Wim was able to recall many elements of both the Junyo Maru and the Pakan Baroe or Pakanbaru railway line history. Combined with my five years of research, I was able to verify many of the aspects of the story.

There are also many WW2 historians, who have had spent their lives researching the second world war, and the sea battles. However, there are fewer that know the stories firsthand from the battles surrounding the former Dutch East Indies. This book records numerous examples of Hellships, but factually recalls the experience of being on a Hellship firsthand. The fact that this is a story of the Junyo Maru, the largest loss of life on a Hellship and the infamous tragic occurrences, make this story relevant for WW2 historians and naval researchers too.

#ww2 #BurmeseRailway #PakanBaroe #Pekanbaru

Dutch School curriculum introduced Hellships to its students

In 2022, the schools in the provinces of Arnhem, Gelderland and North Holland introduced the Hellships into the mainstream curriculum. A series of books are included in the launch, including a cartoon comic book, which summaries the various stories around the second world war in Asian. Willem Punt’s story is prominently featured in all of the stories, as it provides a complete historical record as well as a personal first-hand record of the Junyo Maru, but also life as a POW in the Japanese Camps.

Extracts from the book

Trip from Halifax to Liverpool

Leaving in good weather at the end of summer (maybe August or September), we set sail in the SS Singkep from Halifax, Newfoundland, Canada to Liverpool, England. We were transporting Indian rubber. This may not seem to be a precious cargo, until you consider all the uses for it in wartime: it’s used in the manufacture of boats, cars and aeroplanes.

We crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a convoy of 68 ships, accompanied by a few corvettes. The communication between the ships was conducted purely with flags. That was my new job on the SS Singkep. Every day around noon we all had to signal our position. One day, a joker signalled to me that he was in the Sahara, near Timbuktu. The commander of the convoy did not appreciate this joke at all. The guy was punished and was told in no uncertain terms not to do that again. We were sailing in wartime and tensions were very high as prior crossings had been very deadly. It wasn’t the right time for jokes.

We had to travel at the speed of the slowest vessel in our convoy and there were steam-powered boats with us travelling at only 10 knots per hour. There were over 260 German U-boats in the seas at that time, and any could fire torpedoes at our convoy. We were, quite literally, sitting ducks, as we were travelling so slowly.

We had English destroyer corvettes racing around us. I’m grateful to the corvettes for their service and attempts to keep us safe. Every time the submarine alarm went off, the corvettes rushed through the convoy at high-speed, trying to listen out for and identify the location of German U-boats. We maintained radio silence during the convoy, so that we had a better chance of not being hunted down.

Eerily, I was told we would see the flash of light signalling a torpedo impact before we heard the roar of the explosion, just as you see lightning before you hear the thunder. I didn’t see any explosions, as our convoy was not targeted. However, the German U-boats had obviously attacked previous convoys, as I saw hundreds of bodies in the water. Most of the people floating in the water had died, but sometimes the people were still alive.

Regretfully, in these crossing there were no rescue boats. All boats were instructed not to veer from their own course, not even to pick up survivors. Any ship, which went to help rescue sailors, would probably be torpedoed too, as it would maneuver itself into the firing line. Rescue efforts were strictly forbidden and weren’t attempted. If you survived the blast, you would drown at sea.

Even so, I learnt from the horrific tales of boats being torpedoed. I mulled over who had a better chance of surviving a direct hit. I thought how important it was to choose where you should jump overboard. I knew that you ideally needed to jump overboard at the back, as the torpedoed boat would keep its forward momentum for a while and would crush anyone who tried escaping at the front. I checked and double-checked where the flotation devices were during that trip. I felt safest at the back of the ship near our quarters.

Struiswijk Prison, in Batavia, Java (now called Jakarta, Indonesia)

Struiswijk prison was designed and built by the Dutch. It was a kind of fortress. On the perimeter was a wall, approximately 10 meters high, with a lookout post where two Japanese armed guards kept watch. Inside the wall was a fire corridor, about 20 meters wide.

Behind the fire corridor was a solid wall without windows; that was the back of the actual prison. To get into the prison you first went through high steel doors in the first wall, and then there were two doors in the inner wall. If you can imagine it, the entrance doors were connected to each other by a kind of tunnel.

Once inside the inner walls there were offices, a warehouse and the watch. The centre of the prison was an open area with some trees. It was about the size of a football pitch.

Around this field were barracks converted to lodgings and cells. The inner wall of the prision formed the rear wall of the barracks and the cells were groupsed into blocks. Leen and I were locked in a single cell, in Block J.

In the original Dutch design one cell was intended for just one local prisoner. The dimensions were two and a half meters long, one and a half meters wide and 2 meters high.

The lighting in our cell was an electrical bicycle lamp on the ceiling. We made improvements by using the silver paper from a cigarette packet to reflect the light back into the room. With this we could both play solitaire with a deck of cards in the evening.

During the time that we were in that block we were allowed out three times a day. We could wash and shave at the well. The well was in the middle of the courtyard that belonged to our block. It was an opportunity to go to the toilet and get something to eat. Those excursions took about two hours. Talking to other prisoners from another block was strictly prohibited so we were completely devoid of any news. It was difficult being completely isolated from everything outside our block. This isolation lasted about six months.

It appeared that the Japanese interrogated the inmates for any details or knowledge, which they could use for their war efforts. I saw several inmates taken from our block and they were badly beaten before coming back. Some I never saw again…

The sinking of the Junyo Maru, in the Indian Ocean

(the greatest loss of life on a single Hellship)

In September 1944 a large number of us had to pack up again to leave, taking our few possessions with us. We were told to travel light, as we would need to walk a few kilometres. We went on foot from the camp in the direction of the station. Several people took too much with them and had to abandon them on the way. An armoured train was already waiting for us. About 2,500 men were roughly crammed into that train. There were too many of us to fit inside, so we were hit with rifles butts to get us to squeeze in.

The train left and went towards town. And when it changed tracks I knew exactly here we were going. As a sailor I’d often gone by train to the harbour to town. The train stopped again after half an hour and we had to get out. We all realised where we were: the Tanjung Priok train station at the port of Batavia. By then, I wasn’t the only one to have strong suspicions that we would carry on our journey by ship, as we walked a kilometer or two towards the port.

Whilst walking, I started to think about the logistics of what was going to happen. I said to my friend Leen Sloot, “Watch out, we are going on board.”

I thought about what this would mean to transport so many people in one ship. It seemed so dangerous to me. I wanted to stay as safe as possible and protect my friend Leen. I’m a thinker and tried to take in what was going on around me. I said to Leen “Let’s try to get to the back of the crowd. We need to walk slower than the rest, in order to board last. If the ship is blown up, we must be on deck and not trapped in the hull.”

Although everything was very disciplined the Japanese still found it necessary to act as slave drivers. They were yelling and hitting people to speed them up. Most people were (rightly) afraid of getting a beating and were panicking with fear, so they naturally hurried along.

Despite the Japanese’s sharp control, Leen and I prudently managed to work our way towards the tail of the procession. We pretended to do up our shoelaces and made it look like we were hurrying, but we took smaller steps.

We were led to a quay where the Junyo Maru was anchored. It was a rusty old wreck. At that time, it was considered a huge freighter, I guess around 6,000 register tonnes. We could see the people at the front already boarding the vessel via a wide wooden staircase that was placed against the ship. On board they were literally kicked into the holds, to chase them to the depths of the hull. We discovered that the rear half of the ship was reserved for us.

The front of the ship was loaded with indigenous people, who had been recruited or captured by the Japanese to work for them. The Japanese visited villages and paid the village chief for the men to be used as labourers. If the chiefs refused, the men were taken anyway, and the chiefs weren’t paid. Later, the Japanese also started taking their boys saying they would be given a Japanese education. These people were the cheapest of their labourers and seen as most expendable. They were slave labourers, or romushas. They were all kept far away from us whites and were treated much more harshly than us. The Japanese ensured we made no contact with them.

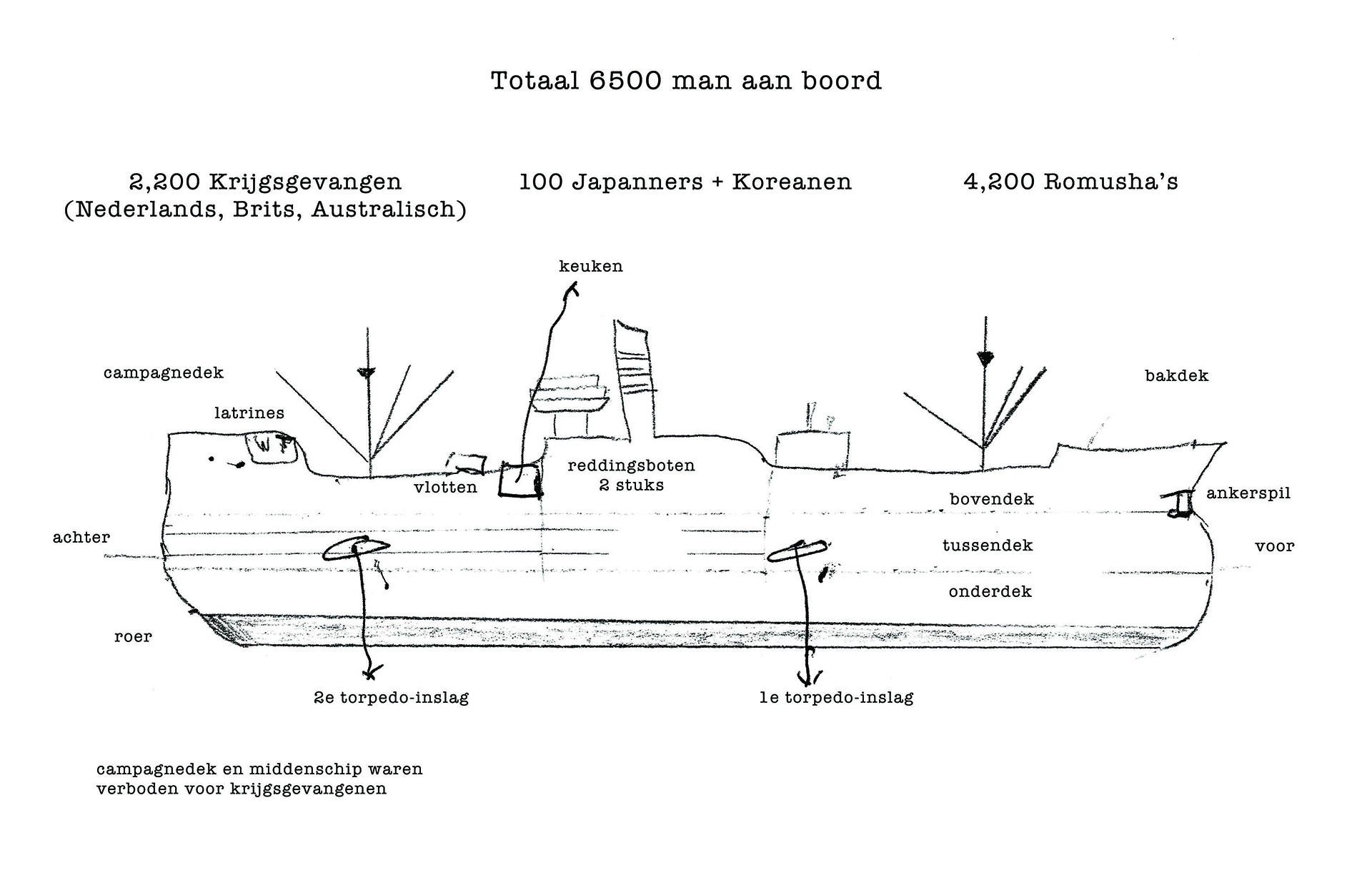

There were approximately 4,000 Indonesians located in the front section of the ship. In the rear part there were around 2,300 allied POWs (mainly Dutch).

The Japanese guards were in the midship area (on the bridge) and on the quarterdeck/poopdeck (at the rear of the ship). I think there were around 200 well-armed soldiers. Both the midship and the poopdeck areas were prohibited for the non-Japanese. […]

The holds were normally divided by two metal platforms, creating horizontal spaces: the top, middle and bottom hold. The bottom hold was sealed as there was probably cargo in it. The mid and top areas were for people.

These two holds were further split into a number of horizontal layers, constructed from wooden buttresses with shelves. The Japanese divided each of these decks into another three layers and thus obtained six layers of people above each other. Each man had to crouch, almost crawling, to get in.

We were housed in the stern, where there were still three vertical holds. In total there were three times six i.e. 18 compartments in the rear part of the ship for the POWs.

My sketch of the Junyo Maru

Source: Nicola Meinders

Work on the Pakan Baroe Railway, Sumatra

After some weeks we were again loaded onto lorries again and taken further inland towards Pekanbaru (Pakan Baroe in Dutch). When we arrived camps 1, 2 and 3 were already finished and had sufficient people to carry out maintenance duties.

The camp where I was brought was called “Camp 4”. Both 3 and 4 were very wet and boggy. The mosquitoes were rife in these two campany and many prisoners contracted the deadly disease malaria. In camp 4 we needed to build a bridge over the river and then carry on building new tracks towards Padang.

We learnt more from prisoners who were already stationed there. They told us that on the whole way from Muara Enim to Pekanbaru there were 16 camps. These were numbered from 1 to 14a, starting in Pekanbaru. I was in a couple of those camps; 4 (Taratak Boeloen), 5 (Loeboeksakat), 7 (Lipat Kian) and 11 (Koeantanrivier).

We were transferred from one camp to another whenever a section of the railway line was completed. A maintenance team was kept behind, and the rest went on. In the camps it was the same old story when it came to medical care – there was none at all. The food remained poor and in short supply. It wasn’t just the POWs whose lives had changed, the conditions for the Japanese were also worse than before.

We also got beaten if the Japanese found the work wasn’t going fast enough.

The railway line work consisted of the following tasks:

- Building embankments of sand

- Laying sleepers

- Laying rails

- Connecting rails with fishplates

- Straightening rails

- Nailing rails on to the sleepers

- Building bridges over rivers

- Collecting already hacked down trees, to be used for building bridges.

The requirement was to build two kilometers of railway line per day. If it seemed that this would not be achieved in any given day, the Japanese became nervous and started screaming and hitting us in order to get to more momentum.

I did, or tried to do, every one of the eight different tasks to lay that railway. There were some things that I was useless at, and I was forbidden to do them after a few short tries. For example, I couldn’t use the heavy sledgehammers properly to hammer large steel nails into the rails of the sleepers. These big nails were needed to hold the sleepers in place. I didn’t have enough strength to hit it the nails hard enough and I almost never hit the nails straight on the head.

Lugging the heavy metal rails from the lorry to the place where they were needed, was also not my forté. The ten meter-long rails were carried on the shoulders of ten men. Since I am not very tall and also do not have broad shoulders, I was more of a hindrance than a help. The metal rails were in the scorching sunshine all the time and were boiling hot. You had to put a cloth on your shoulders otherwise your skin would burn to the bone. I didn’t have a cloth and I was soon reallocated to another task.

I was ordered to carry wooden sleepers around. We carried them in teams of two men to the place where they needed to be. That was fine until one day wet teak sleepers were delivered. I found it impossible to lift them up at all, even with three men. We cheekily ignored these, maybe they are still rotting there… Again, I was rejected and reallocated.

I got a so-called job putting the fishplates in their position. That was a scientific job, which suited me better. I had to measure where the things had to be, every ten meters on both sides. It was a one-man job and it was relatively independent. Since I had to work ahead of the rest of the tracklayers, I sometimes walked a kilometre ahead of the toiling crowd. I walked by stepping from sleeper to sleeper. I had no footwear, so I walked with bare feet. The only clothing I had was a loathsome jute cloth covering my buttocks. In that period, I was dark brown from top to toe.

As I walked ahead, I was far enough out of sight to do a little bit of foraging for food. I remembered seeing indigenous people eating chillies at some point and I decided to copy them. I had no way to cook them, so I taught myself to eat them raw. They burned my taste buds, but at least I was eating something with nutritional content. Nowadays, we know chillies contain lots of vitamins, including high level of vitamin C, which wards off scurvy.

Life and death on the Pakan Baroe Railway in Sumatra

One day I was shaking with cold. The next day I had a strong fever. Then the next day I had no fever. A day later, the shivering started again… This feverish illness continued to repeat itself. A Dutch doctor diagnosed me with Tertian Malaria. He prescribed a lot of cinchona (kina) bark powder to swallow. We were near the former colonial cinchona tree plantations. So there definitely wasn’t a shortage of trees. We whacked the bark off the trees and laid them out to dry in the sun. With a pestle and mortar, we ground them into a dark-brown sand.

The nurses told me that I had to down half a coconut filled with this sand twice a day. That was the only way to get enough quinine into our systems. That was the equivalent to one of those luxuriously, sugar coated quinine tablets.

Quite frankly I did not take that that medicine as faithfully as I should have done, because I just couldn’t force that dry, brown sand down my throat. I believe that my malaria was aggravated by my lack of will power to motivate myself take the medicine regularly.

I became so ill, that they pretty much gave up on me. I was moved to the corner of the barracks, where the sick normally died.

I can remember that I was very sick. I tried to stop flies flying in and out of the mouth of someone next to me. I tried to wake him up, so he would close his mouth. Later I was told that he had already died. As we only had up to 75cm-wide berths in which to sleep, you were very close to the guy next to you. This explains in part, why I tried to swat the flies in my delirious state, as they were also biting me.

One day a Dutch army doctor, by the name of Bakker came to see me. He asked how I was doing. I said I wasn’t doing so well. He suddenly produced ten quinine pills for me. A whole handful! He told me I needed to swallow them with water. He said “swallow these now. I’m going to watch that you take them. No more nonsense this time.” I don’t know why he chose to give me the course of the pills, but I responded well to them. Despite my desperate state in the death ward, I returned to my old place after a number of days. That was a big surprise to my buddies; they thought I was a goner.