The sinking of the Junyo Maru, in the Indian Ocean

(the greatest loss of life on a single Hellship)

In September 1944 a large number of us had to pack up again to leave, taking our few possessions with us. We were told to travel light, as we would need to walk a few kilometres. We went on foot from the camp in the direction of the station. Several people took too much with them and had to abandon them on the way. An armoured train was already waiting for us. About 2,500 men were roughly crammed into that train. There were too many of us to fit inside, so we were hit with rifles butts to get us to squeeze in.

The train left and went towards town. And when it changed tracks I knew exactly here we were going. As a sailor I’d often gone by train to the harbour to town. The train stopped again after half an hour and we had to get out. We all realised where we were: the Tanjung Priok train station at the port of Batavia. By then, I wasn’t the only one to have strong suspicions that we would carry on our journey by ship, as we walked a kilometer or two towards the port.

Whilst walking, I started to think about the logistics of what was going to happen. I said to my friend Leen Sloot, “Watch out, we are going on board.”

I thought about what this would mean to transport so many people in one ship. It seemed so dangerous to me. I wanted to stay as safe as possible and protect my friend Leen. I’m a thinker and tried to take in what was going on around me. I said to Leen “Let’s try to get to the back of the crowd. We need to walk slower than the rest, in order to board last. If the ship is blown up, we must be on deck and not trapped in the hull.”

Although everything was very disciplined the Japanese still found it necessary to act as slave drivers. They were yelling and hitting people to speed them up. Most people were (rightly) afraid of getting a beating and were panicking with fear, so they naturally hurried along.

Despite the Japanese’s sharp control, Leen and I prudently managed to work our way towards the tail of the procession. We pretended to do up our shoelaces and made it look like we were hurrying, but we took smaller steps.

We were led to a quay where the Junyo Maru was anchored. It was a rusty old wreck. At that time, it was considered a huge freighter, I guess around 6,000 register tonnes. We could see the people at the front already boarding the vessel via a wide wooden staircase that was placed against the ship. On board they were literally kicked into the holds, to chase them to the depths of the hull. We discovered that the rear half of the ship was reserved for us.

The front of the ship was loaded with indigenous people, who had been recruited or captured by the Japanese to work for them. The Japanese visited villages and paid the village chief for the men to be used as labourers. If the chiefs refused, the men were taken anyway, and the chiefs weren’t paid. Later, the Japanese also started taking their boys saying they would be given a Japanese education. These people were the cheapest of their labourers and seen as most expendable. They were slave labourers, or romushas. They were all kept far away from us whites and were treated much more harshly than us. The Japanese ensured we made no contact with them.

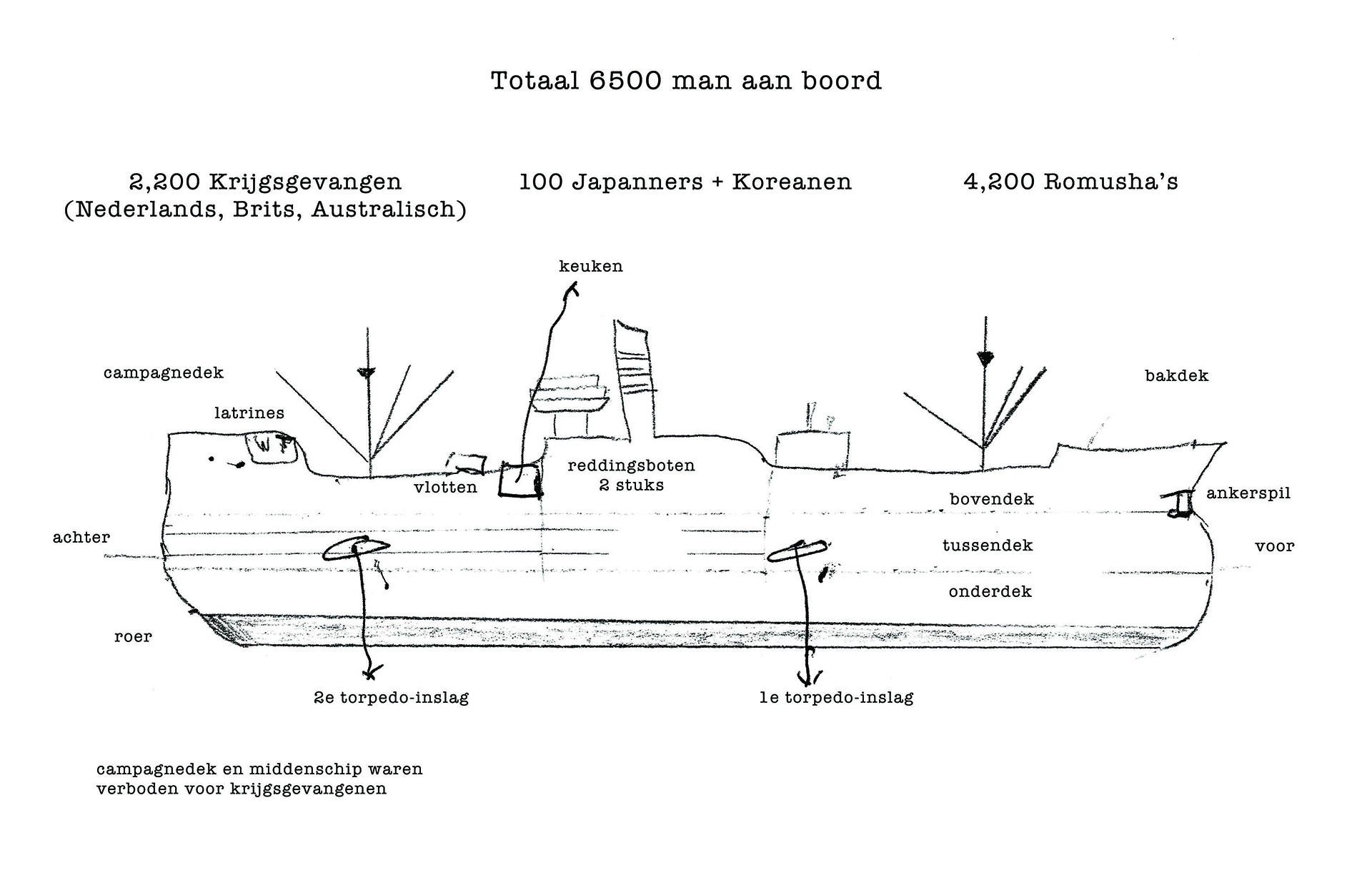

There were approximately 4,000 Indonesians located in the front section of the ship. In the rear part there were around 2,300 allied POWs (mainly Dutch).

The Japanese guards were in the midship area (on the bridge) and on the quarterdeck/poopdeck (at the rear of the ship). I think there were around 200 well-armed soldiers. Both the midship and the poopdeck areas were prohibited for the non-Japanese. […]

The holds were normally divided by two metal platforms, creating horizontal spaces: the top, middle and bottom hold. The bottom hold was sealed as there was probably cargo in it. The mid and top areas were for people.

These two holds were further split into a number of horizontal layers, constructed from wooden buttresses with shelves. The Japanese divided each of these decks into another three layers and thus obtained six layers of people above each other. Each man had to crouch, almost crawling, to get in.

We were housed in the stern, where there were still three vertical holds. In total there were three times six i.e. 18 compartments in the rear part of the ship for the POWs.

My sketch of the Junyo Maru

Source: Nicola Meinders